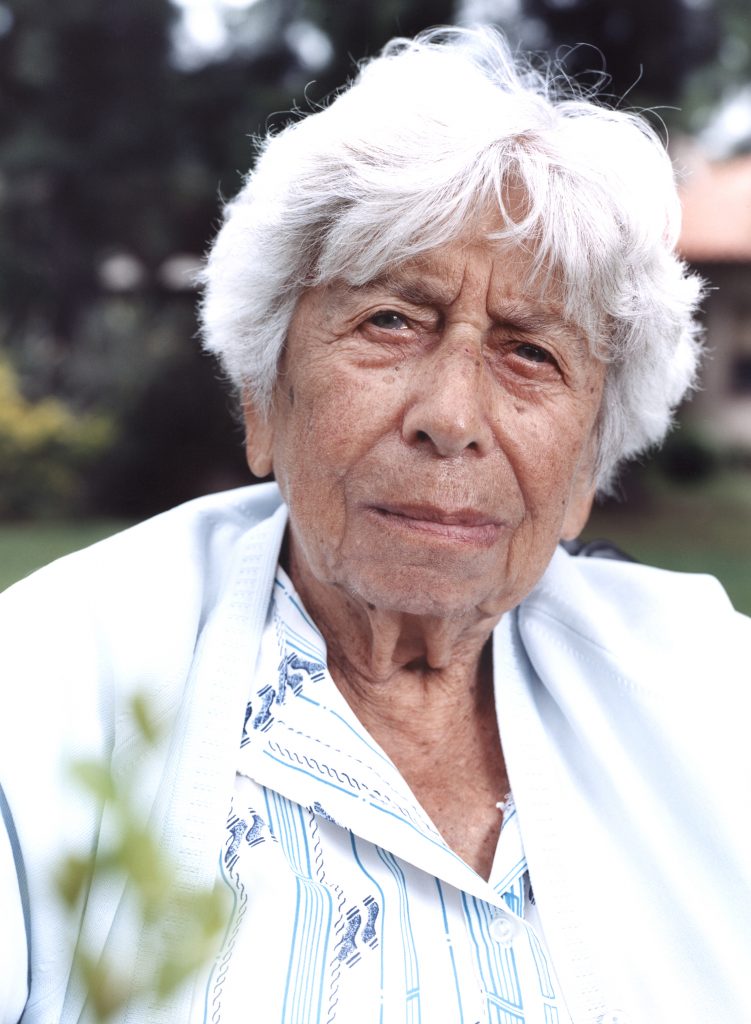

She’s sitting in her wheelchair in room number 117 and wears a cheeky grin. “I’m the youngest here,” she says. Ilse Altmann has a great sense of humour. She doesn’t take the past nor the present too seriously. Her long life has been very turbulent and exciting. If she was to try and remember every last detail and take it seriously, who knows, maybe she wouldn’t be feeling so up-beat.

© Tim Hoppe

Ilse Altmann, named Ilse Margarete Zirker, was born on 14 October 1910 in Berlin. She spells it out: ‘Z I R K E R’. She lived in the northern centre of the city, in the suburb called ‘Gesundbrunnen’. Until she emigrated, until 1938. How was her childhood and upbringing? She can’t remember clearly. Good, she supposes.

„The only thing that let me down was the issue of Arian descent.”

She studied dental medicine at the University of Berlin. “I got a first in all my exams. I succeeded in everything. The only thing that let me down was the issue of Arian descent.” By the time she finishes her studies, the National Socialists have long since risen to power. From then on she works in an established Jewish dental practice as an assistant until it loses its licence. Ilse Altmann tells us that the patients, all of whom were working men, continued to turn up and usually paid a little something for their treatment. Shortly after, her boss emigrated “and died straight away the following day”. What’s that she says? “Yes, that was very sad,” she says and continues without lingering on the subject. “I worked there secretly for another little while and then the practice was dissolved.” This was every day life in Nazi Germany.

„Of course my husband walked across the fields at night so they wouldn’t come and get him at dawn”

She says she has no memory of Nationalsocialism, ”because thank God we weren’t affected personally. Of course my husband walked across the fields at night so they wouldn’t come and get him at dawn.” She just says this casually. Yes, she was afraid that they would come for them in November of 1938. Was that Altmann? Or the other one, her first husband? She can’t really remember. All her memories are in a jumble. When did she get married? “Yes, that’s what I’d like to know”, she says with a chuckle. But then the memories are coming back. “Altmann”. She pauses briefly. “I met Altmann when I went into the Jewish Hospital to train as a nurse, because they needed nurses in England”. That is where she wanted to emigrate. The man whom she had set her heart on and whom she originally wanted to marry was someone else. “He emigrated before I did. We didn’t have enough money to pay for both tickets. So I had to stay behind.” On the crossing to the US he meets a German-American, who later introduces him to his relative, “a very beautiful girl”, she says. She was said to have a lot of money, “so of course he ended up marrying the girl, and I was sat at home.” No big deal. At least from today’s perspective. She laughs. “I couldn’t go to or fro”. At this point she must have decided to go to England on her own. But then she meets Altmann. Due to his sickly mother, her new fiancée doesn’t want to leave the country. When his mother dies, the young couple starts off towards South America.

Her history has no room for emotions

They have to leave Ilse’s mother behind. “She perished. By the time I was ready to come and get her, i.e. by the time I had organised immigration papers for her, she was no longer able to leave the country.” She talks and talks but doesn’t mention her feelings. Her history has no room for emotions. Ilse Altmann loses many relatives in the Shoa. Her brother manages to save himself by escaping to England, others flee to China “and to the strangest places. Some eventually made their way from there to the States.” She and her husband make it to Bolivia at first. But she’s not sure whether it was Altmann, with whom she emigrated. “No, Altmann wasn’t his name. What was his name?” She’s at a loss. Whilst at the same time keeping that cheeky smile on her face. Then she says: “Seems like I always had a fair selection of men”.

But the one with whom she arrives in Bolivia is Altmann, the man to whom she got married. In Berlin, she says. And there they lived together for a while before emigrating. She remembers that they left the country on a ship of the shipping agency ‘Hamburg Süd’ and while she is talking she remembers a ‘nice little incident’. “In order to get our luggage onto the ship, we had to check it in the day before with a man who was very nice. My husband takes out his purse and says: ‘That’s all I’ve got left,’ and hands it over to him, and the man says to him: ‘Don’t be holier than the Pope. You better keep that.’ And then we decided to go for a cup of coffee. My husband got out his purse and found a Thousand Mark bill inside it. He had completely forgotten about it. If that man had spotted the 1000 Marks that would have been the end of us.”

Weeks later they arrive in Chile and take the train from there to Bolivia, as this is the only country that grants them immigration.

Life gets easier and easier

A friend of theirs, a gynaecologist at the Jewish Hospital in Berlin, had also emigrated to Bolivia with his family and he suggests to Ilse and her husband that together they should go to Sucre, as he was to start a new job there. Here, they struggle along, selling “sausages, cheese and so forth”, all without speaking a word of Spanish. Though in time, they learn the language and life gets easier and easier. But then her husband develops “a severe chest infection and we had no money to buy any medication”. A Jewish pharmacist from Vienna helps them. “We couldn’t do an awful lot but he pulled through.’ Then they decide to settle in the countryside. There they live “like in a jungle” in a Jewish settlement. Asked how they felt there, she says drily: “That didn’t matter. The main thing was that we got out. No one gave a hoot about our feelings.” Everything was strange to her, everything was different. Her husband works in an office in the settlement and she herself works mornings as a dentist and as an assistant to the doctor in the afternoons. They also provide indigenous people with medical supplies. Every day, she tells us, they “would queue up asking for medication. They always arrived with match boxes which is where they stowed away the few little pills they received.”

They make their way on foot up to the border

Life in Bolivia is too alien for Ilse Altmann. The toilet is a hole in the ground out in the open air. “There was no shelter other than trees. Primitive.” And then she says, not without a sense of pride, “I always say I emigrated properly. It was something special.” But life in the forest didn’t provide any prospects for the young couple. They are anxious to reach Argentina. They make their way on foot up to the border. Ilse is one month pregnant. Three days and three nights they travel through the jungle. They continue on the train towards Argentina. “Though we did have money, we were too nervous to exchange it” for fear of being discovered. They travel three further days by train, without having anything to eat or drink. “We nearly starved,” she remembers, “and then the Steward came over with a large tray of coffee and rolls. My whole life I didn’t eat as I did then.” Her eyes shine.

Because they look dishevelled from their long journey, the owners of their accommodation in Buenos Aires have to discuss whether they want to rent to those two Germans or not. “We came straight off the train, completely unkempt and starved. But they took us in and we lived there for a long time.” Although as their daughter was born, they move to their own flat and settle in their new home. At last Ilse Altmann doesn’t feel like a stranger any more. Argentina felt “very European”, she says. She no longer works as a dentist. Instead, she now looks after her daughter while her husband is out working. “We were now fully settled”.

At some stage, her husband dies. And she lives alone. To this day, she owns a flat in Palermo, a suburb of Buenos Aires. She misses it since she’s obliged to live in Hogar Adolfo Hirsch due to her inability to walk. Her current partner lives there, Oberholzer. He, too, is a German Jew.

Germany is history

Has she remained a German, after all that has happened to her? She has visited Germany, she says, and everything was very nice. She has nothing negative to say. She doesn’t want to go into it. Germany is history. Is she Argentinian? Ilse Altmann’s answer reflects her attitude to life as a whole: the question of identity is not important to her. She thinks: “Whether German or Argentine – I couldn’t care less.”